The 11 ways going nuclear would be a disaster for Australia

Peter Dutton's plan for nuclear power in Australia will be too late, too expensive, too risky, and is just straight-up unnecessary. Here's 11 reasons why.

As unfathomable as it is, Australia is now having a full-blown nuclear debate. Welcome to the ‘Nuclear Wars’. The ‘Climate Wars’ are still raging, in case you had not noticed.

The arguments against making a wholesale push into establishing an Australian nuclear power industry - as has been proposed by Federal opposition leader Peter Dutton - are many.

For those frustrated, and lamenting the future conversations they will inevitably have with friends and family about going nuclear, I’ve compiled what I think are the most powerful arguments, with links to sources throughout.

1. Dutton’s lack of detail

This isn’t a flaw with nuclear power per se, but it is a flaw with the proposition being put to Australian voters. Peter Dutton’s plan lacks detail.

All we know at this stage - as detailed in Dutton’s media release - are the sites and that the cost of construction will be paid for by the Australian taxpayer. Seven locations around Australia that are currently, or previously have been, host to ageing coal-fired power stations.

We do not know the cost, we do not know which technologies will be used. We do not know the full dates for commissioning. Shadow energy minister Ted O’Brien has also refused to reveal how many reactors, or what level of generation capacity, will be constructed at each of the sites. O’Brien can’t even say how much energy he expects the plants to produce.

This is bad public policy development. Particularly, it’s bad public policy from a Coalition party that previously demanded ad nauseam that the Bill Shorten-led Labor party ‘reveal the costings’ of its climate policy before the 2019 federal election.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that as part of its response to the 2019 election loss, Labor commissioned modelling and costings of its 2022 climate policy platform from energy advisory firm Reputex - while in opposition and paying for the modelling out of party funds.

Dutton and O’Brien now say that because they are now in opposition they do not need to produce modelling, and such work a job for a future government. It’s hypocrisy running rife.

2. Nuclear is too expensive

Nuclear technology is generally just very expensive. It requires highly specialised engineering design and construction teams to build facilities that can meet the significantly higher safety standards necessary to ensure safe operation, which make them capital intensive.

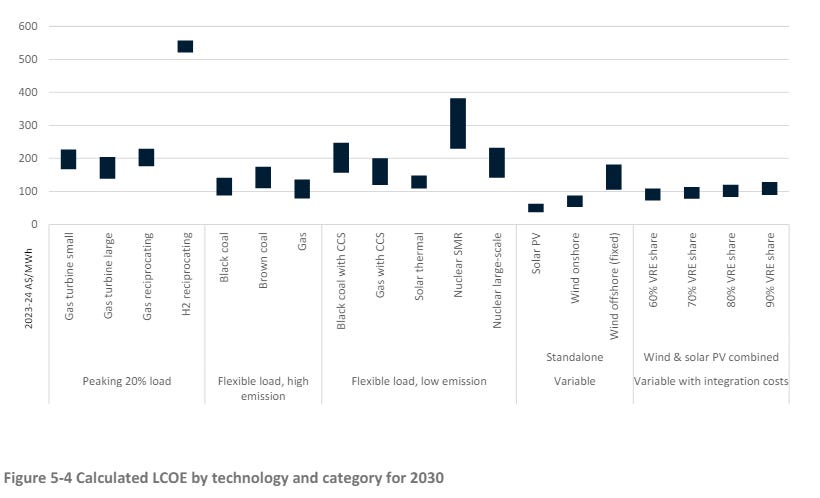

The CSIRO has produced the most publicised estimate of nuclear power costs in Australia, as part of its GenCost series of reports. The 2023-24 edition of the GenCost report estimates large-scale nuclear power in Australia would cost within the range of $155 to $252 per Megawatt-hour. Small modular reactors would be even more expensive.

This compares to the cost of wind and solar, with the additional costs of new network infrastructure and firming capacity added on top, at around $100 per Megawatt-hour. Half the cost of nuclear.

It is not just the CSIRO that says nuclear ranks amongst the most costly sources of new generation capacity. The influential US-based Lazard's Levelized Cost of Energy+ analysis ranked nuclear as the most expensive source of new generation capacity in the United States. Notably, the Lazard analysis found the cost of nuclear power had increased by 49% since 2009, while the cost of wind and solar had declined by 65% and 83% respectively.

You can look at recent experiences in countries with established nuclear industries. The United Kingdom is battling an almost 300% cost overrun at the Hinkley Point C nuclear power station, which has currently racked up a total cost of almost A$90 billion. In the United States, two new units at the Vogtle nuclear power plant - which uses the Westinghouse AP1000 reactors favoured by Peter Dutton - cost more than A$45 billion for the two.

Australia has no experience in building and operating a power station scale nuclear reactor (I touch on this more below), and so would need to invest heavily in building and attracting the skilled workforce and knowledge base required to build a nuclear plant the first time. This increases risks, financing costs and the prospects of cost and schedule overruns that the Australian taxpayer would be accountable for.

The cost of Dutton’s seven nuclear plants will run into the 100s of billions, funds that we could spend now building solar, wind and storage.

3. Nuclear will take too long and be too late

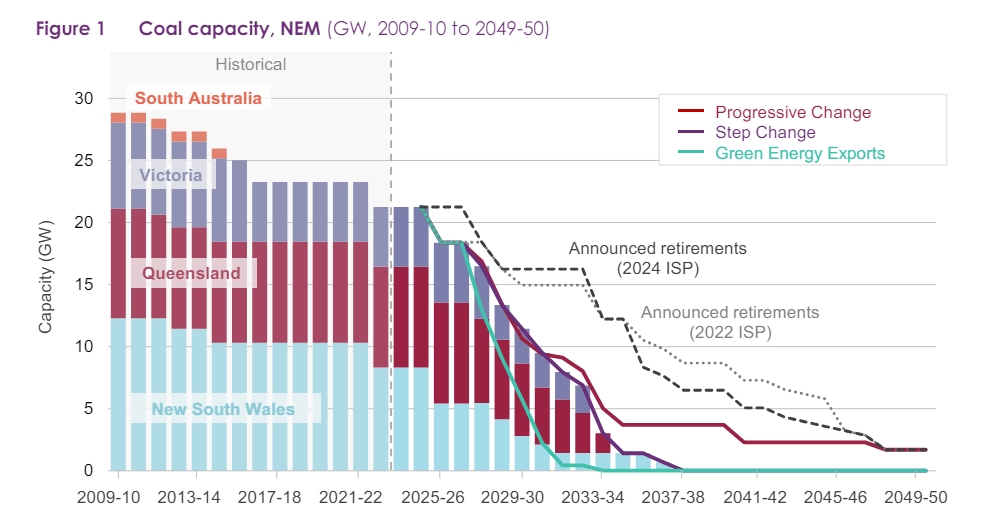

One only needs to consider the likely schedule of retirements of Australia’s coal fired generator fleet. As outlined in AEMO’s recently released 2024 Integrated System Plan, most of Australia’s coal generators will have closed well before 2035.

In its GenCost report, the CSIRO estimates the first nuclear reactors would take 15 to 17 years to get up and running. That’s 11 years to clear the regulatory path, plan and design the plant, as well as secure the necessary land, workforce and equipment, before another four to six years to actually construct it.

International experience suggests that CSIRO’s estimate could be an optimistic estimate of construction times. It’s also an estimate that takes us to 2040 before first nuclear power output in Australia, when all of the coal plants would already have closed.

With Dutton claiming that he could get the first of his nuclear facilities operational by 2035 - again, a highly optimistic timeline - he really needs to explain how he would fill the capacity gap that will grow in the proceeding decade, if not with renewables.

4. Nuclear cannot provide firming capacity

The reality is that Australia is rapidly moving towards a grid that predominantly features wind and solar as major sources of power. In 2023, Australia’s main grids hit 38.6% renewables, almost triple the renewables market share recorded a decade prior.

There’s no contention that renewables are a variable source of power. It’s not a particularly significant revelation to point out that the output of wind and solar go up and down. No one seriously disputes this, and it is why there have been efforts to build up the capacity of energy storage projects that can help smooth out those variations.

A measure of flexibility is a power station’s ‘ramp rate’ - how quickly can a power station increase or decrease its output on demand. AEMO publishes a list of maximum ‘ramp rates’ for the power stations operating in Australia’s eastern states.

The ramp rates of coal plants are slow. For example, the Eraring Power coal-fired station, which consists of four 750MW units, has maximum ramp rate of just 20MW per minute. That means it would take at least 38 minutes to go from zero to full output at each of its four units. The ‘slow’ response rate of coal plants has contributed to their financial demise, as they are unable to avoid the periods of high renewables and low wholesale electricity prices.

Compare this to a 665MW hydroelectric unit at the Tumut power station. It has a ramp rate of 320MW per minute. That’s full capacity in just over two minutes - super fast and ideal for responding to fluctuations in wind and solar output.

Better yet, several big battery projects can hit full capacity within seconds.

So where does nuclear sit? According to the OECD’s Nuclear Energy Agency, optimistic estimates suggest modern nuclear plants have a maximum ramp rate equivalent to 5 per cent of full output per minute. This puts nuclear squarely in the same territory as coal power - inflexible and unable to respond to the variability of a grid that features more and more renewables.

As a more specific example, Westinghouse also lists the ramp rate of its AP1000 reactor as 5% of rated output.

As former chief of the ACCC Rod Sims recently pointed out, if the construction of many large-scale nuclear facilities proceeds, it will require the increased curtailment of wind and solar output to avoid the challenges currently faced by coal plants.

As nuclear power plants lack the flexibility needed to ramp down their output on days when we have abundant wind and solar generation, those renewable generators will be forced to cut their output. Likewise, as nuclear cannot rapidly ramp up output in response to wind and solar supply variations, we will still need to build supplies of firming power - being gas, hydro or battery storage.

5. The nuclear plan hurts investment in renewables

What Dutton has proposed is an unprecedented government intervention in Australia’s energy market. Depending on the outcome of the next Federal election (and several more thereafter), Australia’s future electricity grid could look radically different.

For prospective investors in new wind, solar and storage projects, the uncertainty that has now been created by Dutton’s nuclear proposal - along with his plan to abandon Australia’s 2030 emissions targets - eliminates any confidence they may have had to make those investments. The future is now just too uncertain.

But we need that new investment in wind and solar projects to fill the gap left by closing coal plants, we need it to help keep energy prices down and crucially we need it to achieve long-term reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Dutton’s nuclear plan could therefore interfere with the energy transition.

As the interim CEO of the Clean Energy Investor Group, Marilyne Crestias, said recently:

”A stable and predictable policy environment is essential for attracting and retaining the significant capital required to achieve our renewable energy targets. Substantial changes of policy direction would risk derailing the momentum we have built for Australia’s decarbonisation journey.”

6. Nuclear has a (very) long-term waste issue

Radioactive waste stays radioactive for a very long time. Thousands and thousands of years. A position paper published by the International Atomic Energy Agency indicated that some nuclear waste remains dangerous for so long - thousands of years - any form of permanent storage is not actually realistic. We simply cannot guarantee that it would remain contained and safe for such a long period.

Nuclear waste facilities need to be built in geologically static locations - places that will not shift or change and risk the leakage of dangerous nuclear waste. As an example of the types of facilities needed to store spent nuclear fuel, Swedish company SKB recently completed a storage site that is embedded 500 metres into bedrock and built to last for 100,000 years.

I have no doubt that Australia could build such a facility. But it will take so long for spent nuclear fuel to return to safe levels, that we actually have to think about how to communicate to future civilisations - who may have developed new languages and cultures - about the dangers held within nuclear waste storage sites.

By adopting nuclear power, Australia would be contributing to a potentially lethal waste legacy, that is a risk to not just current generations, but generations of people unfathomably far into the future.

7. Australia lacks nuclear expertise

One major barrier to Australia’s adopting nuclear power is that we have zero experience in the design, construction and operation of a nuclear facility.

Nuclear advocates point to the existence of the OPAL reactor at ANSTO as evidence of Australia’s established nuclear capabilities. The OPAL reactor is a 20MW research reactor. This is tiny in comparison to the reactors used within power stations. The Westinghouse AP1000, for example, has a 3,400MW thermal reactor - 170 times larger than the OPAL reactor.

Arguing that the OPAL reactor demonstrates Australia has sufficient nuclear skills is like saying that because I have solar panels on my roof at home, that I have the expertise necessary to operate a grid scale solar facility. I’m do not.

I don’t question Australia’s ability to build up that skill base, nor the benefits that would come with the employment opportunities for high-skilled workers. The question is whether the investment is necessary given we have already made those investments in skilling up workers for solar, wind and storage technologies.

8. The sites may not even be available

Central to Peter Dutton’s nuclear plan is the idea that sites that currently or have previously been host to coal-fired power stations can be repurposed for nuclear power. This makes some intuitive sense: the sites already feature network infrastructure and it would be prudent to reuse this infrastructure for future projects.

What has become quickly evident is that Dutton has not spoken with the energy companies that currently own and use these sites.

AGL Energy already has major plans for the site of the former Liddell Power Station, including energy storage and solar panel manufacturing. Likewise, EnergyAustralia has plans for a massive battery project at the Mount Piper site, which also made Dutton’s list.

As an indication of how out of step Dutton’s plan is with Australia’s energy industry, he has flagged the potential of using Constitutional powers to compulsorily acquire the sites from their existing owners.

Dutton’s plan requires the derailment of planned investments in new zero emissions infrastructure and the taxpayer footing the bill for forced land acquisitions.

9. Small Modular Reactor technology is not ready

In his press release announcing his nuclear policy, Dutton indicated that up to two of his proposed nuclear power plants would be Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) - including his earliest plant in 2035.

As it currently stands, there are just two operational SMRs; one contained within a Russian floating power station moored off the arctic port town of Pevek and a Chinese plant in Weihai. Between these two plants there is a grand total of 280MW of operational SMR capacity. Australia has several solar farms that each have a higher rated capacity than this.

There’s heaps of evidence that shows SMR technologies are unproven at scale - including from ANSTO - and it is particularly risky for Dutton to count on SMR technologies to deliver his first nuclear plant.

10. Nuclear lacks social licence

The social licence challenge for nuclear is probably the most self-evident, and it relates to each of the above flaws. Conceptually, many Australians can support the idea of a highly-technical zero emissions source of power.

But alongside that acceptance, there’s an underlying trend that suggests Australians wouldn’t want to live anywhere near one. Crucially, support for renewable technologies is substantially higher than nuclear power.

As polling undertaken for Nine papers shows - ‘renewables in general’ have a net 66% favourability ranking amongst voters. This compared to just 8% net favourability for nuclear power - with only coal power ranking lower at 2%.

Community opposition is reflected in the positions of the relevant state governments. Every relevant State government has indicated its opposition to nuclear energy - with several states having their own prohibitions in place.

There are just too many flaws in the nuclear plan to actually win hearts and minds. Meanwhile, renewables have achieved widescale acceptance by a broad section of the Australian community.

11. When nuclear goes wrong, it goes very wrong

I’ve deliberately left this point to last. Arguably it is the most sensational, but it cannot be ignored entirely, because catastrophic nuclear disasters have happened. The underlying problem is that nuclear physics often pushes the limits of human understanding and our abilities to control complex systems.

The Chernobyl disaster is an example of what can happen when hubris goes unchecked. Certainly, the world learnt a lot of lessons from the Chernobyl incident, especially how to avoid the cultural problems of a Soviet regime more concerned with avoiding potential embarrassment than safety.

But the dangers of nuclear cannot be entirely mitigated. The 2011 Fukushima disaster highlights the inherent risks posed to nuclear plants by the uncontrollable forces of nature. While the Fukushima incident wasn’t triggered by a failure of the nuclear plant, the impacts of the causative Tsunami were so much larger due to the significant risk that the mere presence of a nuclear power plant presents.

While thankfully the worst-case scenarios were avoided, there is a lasting legacy from both the Chernobyl and Fukushima incidents. Due to the risks posed by radiation, the town of Pripyat in Ukraine and several towns within the Fukushima prefecture remain no-go areas.

As we well know, Australia is not immune from extreme natural events. The chances of an Australian nuclear accident are very low. But not zero. The catastrophic scale of that albeit unlikely risk poses an unnecessary risk to the Australian public.

If a solar farm, or a wind turbine or even a battery project fails, the results can be dramatic, but the impact is minuscule compared to the long-term and wide-reaching impacts of a nuclear plant failure.

There’s a reason why nuclear power is currently illegal in Australia.

I am not sure it helps to take Dutton seriously and cooperate by making the debate about the merits and problems with nuclear as if the LNP were serious; the focus should be on their continuing support and encouragement for climate science denial and saving of fossil fuels from global warming.

I don't think they care if any nuclear plants get built or not; the advantage of the LNP nuclear 'policy' is entirely near term, a spanner in the spokes of RE as it gains momentum. That requires no actual nuclear power plants. It is political theatre more akin to Big Wiz flammery than actual policy. It is not even promoted as a better way to reach zero emissions sooner, it is promoted as a way to prevent Renewables and save the fossil fuel economy from zero emissions policy.

These people have never shown any commitment to zero emissions, ever. At every point they have opposed and objected and sought to undermine them, with calls for curbing Australian fossil fuels attributed to 'appeasing inner city green elites' rather than about the top level science based expert advice.

Indisputable and great presentation. Congratulations. ✔

Just one thing wrong with it: the morons who vote to the Right in Australia will never read it.